- Key Takeaways

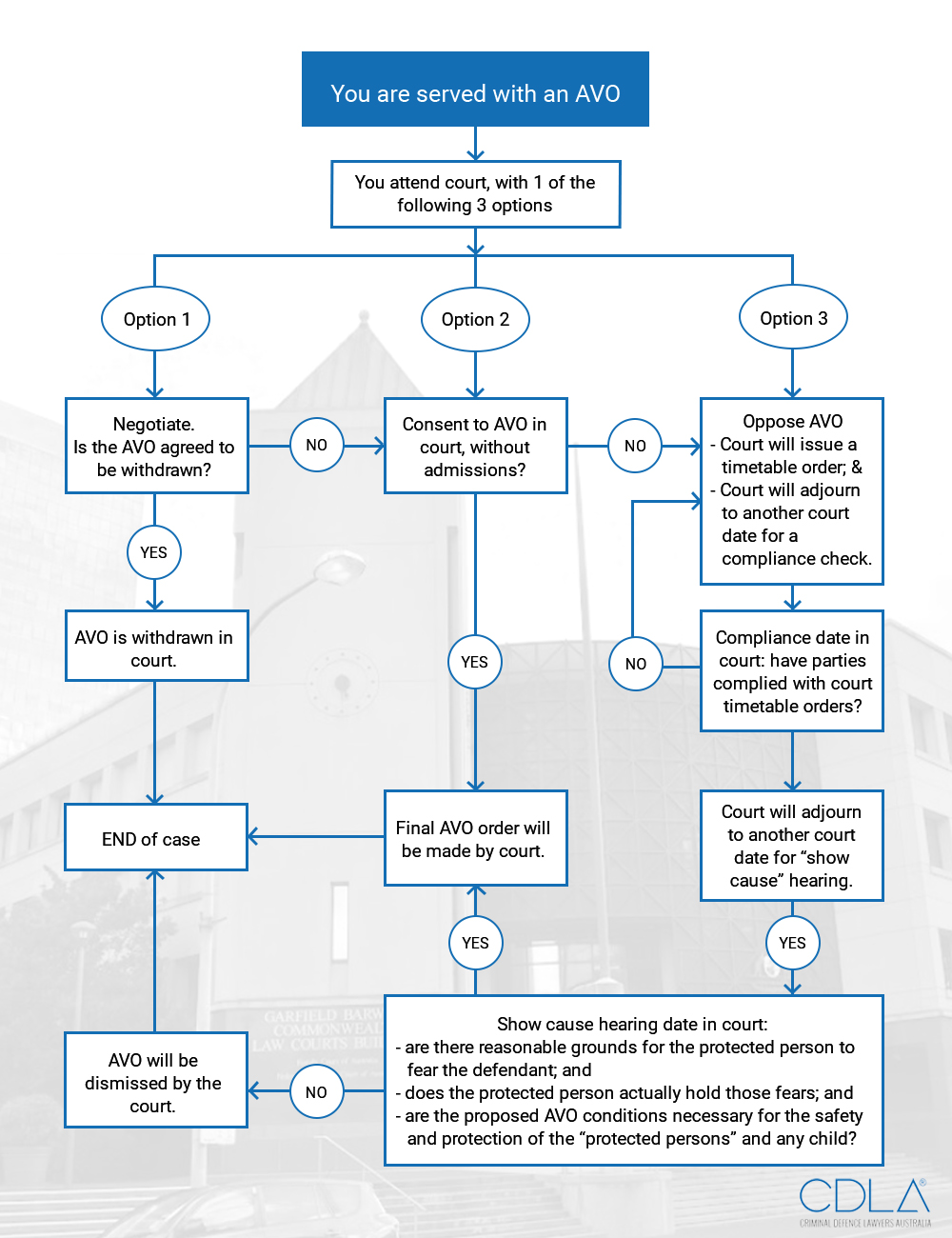

- AVO Court Process

- What is an AVO? Do I Have To Go To Court for an AVO?

- How Serious is an AVO?

- How to Get an AVO Dismissed or Dropped

- Lapsing AVOs

- Defending an AVO | What Evidence is Needed for an AVO?

- Australia AVO: Personal Violence Order NSW vs Domestic Violence Order NSW

- A Police Officer Must Make an Application for an AVO in Certain Situations

- AVO Conditions NSW

- Negotiating an AVO

- AVO Application: Guide on How to Get an AVO | Grounds for AVO

- Who Can Apply for an AVO?

- False or Misleading AVOs

- How to Revoke or Vary AVOs

- If a Child is Named as a ‘Protected Person’ in the AVO

- Who Can Revoke or Vary an AVO?

- How to Remove a Child’s Name From an AVO

- Breach of AVO

- Consequences of an AVO: What Happens After an AVO?

- How to Appeal the Children’s Guardian Decision to Cancel a Working With Children Clearance?

- What is an Interim AVO?

- How Long Does an AVO Last For in NSW?

- Property Recovery Orders in AVO’s

- How to Get a Property Recovery Order in an AVO Case

- What Does a ‘Property Recovery Order’ Allow You to Do?

- What Happens If the Other Person Doesn’t Comply With the ‘Property Recovery Order’?

- What Happens if the ‘Protected Person’ Named in an AVO Doesn’t Attend Court?

- What Happens if the Defendant Named in an AVO Doesn’t Attend Court?

- What Happens if You Fail to Comply with Court Orders in an AVO Case?

- Is an AVO a Criminal Conviction?

- Does an AVO Go on Your Record?

- How Long Does AVO Stay on Record?

- Can you Travel Overseas with an AVO?

- Example of the Court Making a ‘Timetable Order’ in AVO Cases

- How to Get the Other Side to Pay Your Legal Costs in AVO Cases

- Types of Cost Orders in AVO Cases

- Example of Getting Legal Costs Awarded in An AVO Case

- Can the Defendant Get Costs Awarded if the ‘Protected Person’ Named in the AVO Fails to Attend Court or Doesn’t Want the AVO?

- What Happens at an AVO Hearing?

- Can I Appeal an AVO?

Share This Article

ArrayWritten by our criminal lawyers Sydney team, this article is a guide and not to be taken as advice.

- Key Takeaways

- AVO Court Process

- What is an AVO? Do I Have To Go To Court for an AVO?

- How Serious is an AVO?

- How to Get an AVO Dismissed or Dropped

- Lapsing AVOs

- Defending an AVO | What Evidence is Needed for an AVO?

- Australia AVO: Personal Violence Order NSW vs Domestic Violence Order NSW

- A Police Officer Must Make an Application for an AVO in Certain Situations

- AVO Conditions NSW

- Negotiating an AVO

- AVO Application: Guide on How to Get an AVO | Grounds for AVO

- Who Can Apply for an AVO?

- False or Misleading AVOs

- How to Revoke or Vary AVOs

- If a Child is Named as a ‘Protected Person’ in the AVO

- Who Can Revoke or Vary an AVO?

- How to Remove a Child’s Name From an AVO

- Breach of AVO

- Consequences of an AVO: What Happens After an AVO?

- How to Appeal the Children’s Guardian Decision to Cancel a Working With Children Clearance?

- What is an Interim AVO?

- How Long Does an AVO Last For in NSW?

- Property Recovery Orders in AVO’s

- How to Get a Property Recovery Order in an AVO Case

- What Does a ‘Property Recovery Order’ Allow You to Do?

- What Happens If the Other Person Doesn’t Comply With the ‘Property Recovery Order’?

- What Happens if the ‘Protected Person’ Named in an AVO Doesn’t Attend Court?

- What Happens if the Defendant Named in an AVO Doesn’t Attend Court?

- What Happens if You Fail to Comply with Court Orders in an AVO Case?

- Is an AVO a Criminal Conviction?

- Does an AVO Go on Your Record?

- How Long Does AVO Stay on Record?

- Can you Travel Overseas with an AVO?

- Example of the Court Making a ‘Timetable Order’ in AVO Cases

- How to Get the Other Side to Pay Your Legal Costs in AVO Cases

- Types of Cost Orders in AVO Cases

- Example of Getting Legal Costs Awarded in An AVO Case

- Can the Defendant Get Costs Awarded if the ‘Protected Person’ Named in the AVO Fails to Attend Court or Doesn’t Want the AVO?

- What Happens at an AVO Hearing?

- Can I Appeal an AVO?

Key Takeaways

An AVO can get dismissed in court if the other party fail to comply with the orders to serve and file their evidence on time, or through negotiations between the parties, or if the protected person or his/her representative fail to prove that the protected person has reasonable grounds to fear, and actually fears from the defendant (and if the AVO orders are considered necessary for the safety and protection).

The defendant can then seek for his/her legal costs to be paid by the other losing party. This guide outlines everything you need to know about AVOs in NSW and Australia, including how to revoke or vary an AVO order, how to recover property from the protected person’s home, how to defend AVOs, your options in AVO cases, consequences of breaching an AVO, consequences if one party fails to comply with a court order, consequences of having an AVO against you, and how to appeal an AVO order made by a local court magistrate.

AVO Court Process

What is an AVO? Do I Have To Go To Court for an AVO?

If you are served with an AVO, you will be required to appear in court.

An ‘AVO’ is an abbreviation for ‘Apprehended Violence Order’.

An AVO can be a private AVO or police AVO. These are considered civil proceedings in court, not criminal proceedings. It can only become a criminal proceeding if an avo is breached -an avo breach is a criminal offence.

However, having an AVO does have its consequences- it affects family court proceedings in child custody disputes, working with children clearance checks, firearms licence/permit and tenancy agreement.

AVO applications are made by taking out an avo to protect a person(s) from another person.

An AVO order restricts or prohibits a defendant from contacting or from doing certain things to the person(s) who’s in need of protection referred to commonly as the ‘protected person’ in the AVO. This is achieved by the terms of the AVO conditions in NSW.

For example, a defendant named in an AVO can be restricted from contacting or approaching a ‘protected person’ named in the AVO. This restriction will also cover to protect any children of the ‘protected person’ (even if that child is also the defendant’s child).

A police AVO is an AVO issued by police on behalf of the protected person, and is usually related to a criminal charge that the defendant is also facing. Common charges relating to AVOs include

assault charged, intimidation charges, threat or damage property charges.

A private AVO will normally NOT be related to a criminal charge.

What this means, is that usually, if you’re issued with an AVO from police, you will also be charged with a criminal offence by police. The criminal charge and AVO are separate legal proceedings, but can and often do run together at the same time in court as they involve the same alleged victim(s).

If you’re issued with a private AVO, it will not be served by police. It will be served to you privately, and you won’t be charged with a criminal offence.

Although uncommon, police can and sometimes do decide NOT to file a criminal charge against the defendant, yet still issue and serve an avo police order on the defendant. This is usually where there is weak evidence against the defendant.

If you’re served with an AVO, it will either be in the form of a provisional avo, application for avo or interim avo. the AVO will never state the protected person residential address.

The courts allow a protected person or defendant in AVO hearings to have their chosen support person sit near them when giving evidence in court. You may exercise this option at your own discretion.

The relevant legislation on AVO’s in NSW is the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW).

In other States such as Victoria, an AVO is called either a family violence restraining order or personal safety intervention order. These are referred to as an intervention order. These orders can also be referred to as an interim intervention order.

How Serious is an AVO?

An AVO should be taken very seriously for a number of important reasons you should be aware of. Firstly, breaching an AVO condition will result in a criminal offence carrying a penalty of imprisonment and a permanent conviction on your police record. Secondly, an AVO against you will affect child custody disputes in family court proceeding afterwards. Thirdly an AVO can affect your employment and working with children check clearance. Fourthly, an AVO precludes you from ever getting a firearms licence. Lastly, if you are renting premises, it can result in termination of a tenancy agreement.

In addition, a breach of an AVO offence that is domestic violence related requires a sentencing Judge to impose full time detention or supervision, which is a very serious penalty.

If ever someone, later in life, makes a complaint to police against you, police will likely treat the allegation more seriously after seeing on their record that you have or had an AVO against you.

Having an AVO in the past or present will also affect your ability to get bail if ever faced with a criminal charge unrelated to the AVO, later on in life.

It is important to know the comparison between a final AVO, a provisional AVO, and an interim AVO.

How to Get an AVO Dismissed or Dropped

An apprehended violence order can dismissed or dropped by:

- Negotiating with the parties seeking an undertaking which is a non-enforceable agreement that the defendant will agree to the conditions sought in the AVO, or

- Negotiating with the parties by writing to them seeking the withdrawal of the AVO completely by pointing out their weaknesses, offering not to seek legal costs if the other party withdraws the AVO, or

- Seek the dismissal of the AVO by the court on the basis that the other party has failed to comply with any court orders previously made. i.e. if the other side has failed to file and serve their evidence on time, or

- Seek the dismissal of the AVO by the court on the grounds that the other party (protected person) failed to appear in court when required, or

- Seek the dismissal of the AVO by the court on the grounds that the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO does not actually hold fears (applicable if no child is named in the AVO), or

- Seek the dismissal of the AVO by the court on the grounds that the other side have insufficient evidence to prove the allegations on the balance of probabilities and/or the AVO conditions are not necessary for the safety and protection of the ‘protected person’.

The Magistrate can decide not to require parties to comply with orders to serve written statements or evidence to the other side if convinced it would be “in the interest of justice”.

Possible examples where the Magistrate may dispense with the requirement for either or both parties to serve written statements is if either are illiterate, don’t comprehend English, or suffer from a mental health illness.

Lapsing AVOs

The Specialist Family Violence List Pilot Local Court Practice Note is yet one way to get an AVO dismissed early in the proceedings. A lapsing AVO works by adjourning the AVO on an interim basis for a period of time. If there is no breach during the said period of time, the AVO is agreed by the prosecution to be withdrawn and dismissed by the court.

While the AVO is in force on an interim basis, the court may order that the defendant partake and complete counselling or other intervention programs and services.

Lapsing AVO’s can be made by limited courts at the moment, including Downing Centre Court, Blacktown, Newcastle, Moree and Gunnedah circuit (not including Tamworth) courts.

The major benefit of a lapsing AVO avoids the court making a final AVO against a defendant.

Lapsing AVOs are limited to AVO proceedings that do not have an associated criminal charge. This can include private AVOs and police AVOs.

When considering whether or not to order a lapsing AVO, the court will consider the following factors:

- Is the lapsing AVO by consent of the parties?

- Views of the person in need of protection.

- Has the person in need of protection received independent legal advice or engaged in a support service?

- What is the nature of the relationship between the person in need of protection and defendant?

- Is there any reconciliation between the person in need of protection and defendant?

- The gravity of seriousness of the allegations outlined in the grounds of the AVO application.

- What are the AVO conditions sought?

- Has a lapsing Avo previously been sought?

- Are there any affects associated from imposing an interim AVO order instead of a final order?

- Is the defendant getting counselling or treatment?

The interim AVO can be delisted at any stage prior to the next court date. This can be re-listed by application from any of the parties for purposes of asking the court to fix a show cause hearing date.

Defending an AVO | What Evidence is Needed for an AVO?

You can fight or defend an AVO in court by expressing to the court that you oppose the AVO becoming final. The person trying to enforce the AVO against you bears the onus of proof on the balance of probabilities.

You will successfully defend an AVO if:

- The protected person named in the avo, or police, fail to prove the allegations in the avo on the balance of probabilities; or

- The court is not convinced on the balance of probabilities that:

- The ‘protected person’ actually fears from the defendant, and has reasonable grounds to fear the defendant committing a personal violence offence or engage in intimidation or stalking; and

- The court considers such conduct is enough to make the AVO orders/conditions final.

If an interim AVO has been active for a lengthy period before the AVO proceedings conclude, the court may dismiss the AVO if there’s been no avo breaches during the interim avo period. This is because the court can then conclude that the ‘protected person’ has no reasonable grounds to fear.

Australia AVO: Personal Violence Order NSW vs Domestic Violence Order NSW

The two main types of apprehended violence orders (AVOs) are:

- Apprehended Domestic Violence Order (DVO); or

- Apprehended Personal Violence Order (PVO)

What’s the Differences Between an AVO, DVO & PVO?

An Apprehended Domestic Violence Order (DVO) in NSW applies if there’s a “domestic relationship” between the defendant and ‘protected person’ named in the AVO.

A “domestic relationship” includes:

- Marriage (this includes an ex);

- Intimate relationship (sexual or not) (this includes an ex);

- If you are living or were living in the same home;

- Relative i.e. any blood relation, including half brother or sister

An Apprehended Personal Violence Order (APVO), also known as a personal protection order in NSW is very similar to a Domestic Violence Order. However, a Personal Violence Order only applies in circumstances where the defendant and ‘protected person’ named in the AVO don’t have (and never had) a ‘domestic relationship’.

DVO vs PVO?

An avo domestic violence order automatically includes any children of the ‘protected person’ as ‘protected persons’ named in the AVO.

A child named in the AVO can have far reaching consequences on a defendant in any family court proceedings involving child custody or parenting orders later on.

A personal violence order, on the other hand, does not automatically include any children of the ‘protected person’ named in the PVO. For that reasons its often better to have a PVO than a DVO against you.

Another significant feature of a PVO that a DVO doesn’t have- is that in a personal violence order application, the court will be required to refer both parties (defendant and protected person) to mediation, in an attempt to resolve the AVO before finalising the AVO.

Mediation is then conducted by the Community Justice Centre who then produce a report to the court on the mediation outcome. After considering this report, the court can then decide on what to do with the personal violence order application. This can result in the PVO being dismissed before it even goes to hearing.

A Police Officer Must Make an Application for an AVO in Certain Situations

Under section 49 Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW), Police MUST apply for an AVO court order (or avo restraining order) in an attempt to protect the ‘protected person’ from the defendant in the following circumstances:

- Where the police officer suspects that a domestic violence offence or intimidatory conduct by the defendant has occurred, is occurring, or is likely to occur; or

- The defendant has already been charged and facing court for a domestic violence or intimidation/stalking offence.

However, the police do not need to make an application for an AVO if:

- The ‘protected person’ is 16 years or older at the time; and

- The police officer investigating the case believes that the ‘protected person’ intends to make an AVO application or where the police officer believes there’s ‘good reasons’ to not make an AVO application against a defendant.

If the police officer decides not to make an AVO application for ‘good reasons’, the police officer will have to provide written reasons on file. Generally, ‘good reason’ WON’T include a situation where the alleged victim is reluctant to apply for an avo.

AVO Conditions NSW

AVO conditions restricts & prohibits the defendant named in the AVO from doing certain things in respect to the protected person named in the AVO.

A Court will only impose AVO conditions that are considered ‘necessary or desirable’ to ensure the safety and protection of the ‘protected person’ and any child of that person. This is reflected in section 35 and 17 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW).

All AVO applications contain the standard mandatory conditions. They can also come with additional conditions if it’s ‘necessary or desirable’ to ensure the safety and protection of the ‘protected person’ and any child.

Mandatory AVO Conditions 1(a), (b) and (c)

The AVO mandatory conditions comprises of conditions 1(a), (b), and (c) prohibiting the defendant from engaging in the following conduct against the protected person or any person he or she has a domestic relationship with:

- Threaten or assault;

- Intimidate, harass or stalk;

- Recklessly or intentionally damage or destroy any of their property, or any property that’s in the ‘protected persons’ possession. This includes the property of anyone with whom the ‘protected person’ has a domestic relationship with. This also protects the protected person’s pet animal ie dog or cat.

A breach of any of the above AVO conditions amounts to the offence of breach of AVO which attracts heavy criminal penalties, including up to two years imprisonment in the Local Court.

Additional AVO Conditions

The AVO can in some cases impose additional conditions prohibiting the defendant from engaging in one or more of the following conduct against the protected person or any person he or she has a domestic relationship with:

- Approach or contact them in any way, unless the contact is through a lawyer, or to attend accredited or court-approved counselling, or mediation and/or conciliation, or as ordered by the court about contact with children, or as agreed in writing between the parent(s) about contact with children, or as agreed in writing between the parent(s) for the children about contact with the children.

- Access to:

- Any premises that the ‘protected person’ lives in;

- Any place that the ‘protected person’ works;

- Any place or premises the ‘protected person’ frequents

- Approaching the ‘protected person’ or any place/premises within twelve hours of drinking alcohol or taking illicit drugs;

- Finding or trying to find the ‘protected person’;

- From having a firearms or prohibited weapons;

- From interfering, deliberately damaging or destroying the ‘protect person’s’ property;

- Certain behaviour that may affect the ‘protected person’.

Breach of an AVO condition in any form such as interim, provisional or final AVO is a crime, attracting heavy criminal penalties, including up to two years imprisonment in the Local Court, according to section 14 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal) Violence Act 2007 (NSW).

Negotiating an AVO

An AVO can be negotiated with the other side, including the police or applicant. An experienced AVO lawyer can negotiate seeking the withdrawal of the AVO on condition of an undertaking that the defendant will agree to not engage in the kind of conduct sought in the AVO. This option was more commonly used many years ago, but is less common to date.

Alternatively, the AVO can be negotiated by seeking a lapsing AVO by adjourning the AVO on an interim basis for a period of time on the agreement that the AVO will be withdrawn and dismissed in court at the end of that period in the event of there being no breach in the mean time.

Another avenue to negotiate an AVO is to consider the option of consenting to the AVO conditions sought, but on the condition that the AVO allegations are not admitted to with agreeable conditions over an agreed period of time. Here you can try to negotiate all conditions, period of time without any admissions to the allegations put by the other side, which is a common approach because it results in the AVO being final on the same day, concluding the AVO proceedings.

AVO Application: Guide on How to Get an AVO | Grounds for AVO

Here is how to get an AVO in New South Wales:

- An AVO application must first be made.

- The AVO application can be made at the local court registry or at your nearest police station.

- If the AVO application is approved, it becomes a provisional AVO which lasts for 28 days- the defendant can be arrested and charged if the defendant breaches the provisional AVO orders/conditions.

- A court date will usually be set within 28 days from when the provisional avo is made.

- The court can turn this provisional AVO into an ‘interim AVO’, which effectively continues the AVO to the next court date if the matter isn’t finalised on the first date.

- The AVO will then continue on an interim basis until the court either:

- Turns it into a final AVO; or

- Dismisses the AVO; or

- Revokes the AVO; or

- If police or applicant of the AVO end up withdrawing the avo.

How to Get a Private AVO

Here is how to get a private AVO against a person:

- Complete and file an application for an AVO form at the local court registry,

- This will be reviewed by the court registrar or Magistrate, who will process it into a provisional AVO if satisfied that there are reasonable grounds,

- The private AVO form, if approved will become a provisional AVO,

- The provisional AVO must be served to the defendant or defendant’s legal representative for it to be enforceable.

How to Get a Police AVO

Here is how to get a police initiated AVO against a person:

- A senior police officer completes and files an application for an AVO form, which is filed with the local court registry,

- The senior police officer can only apply for and approve a provisional AVO if there’s reasonable grounds for it,

- Alternatively, on a provisional AVO application can be approved by a local court registrar or Magistrate at the request for a police officer if there’s reasonable grounds for it,

- The provisional AVO must be served on the defendant named in the AVO for it to be enforceable.

Can an AVO Application b Refused or Rejected?

If the AVO application is made by someone other than police, a Magistrate or Registrar of the local court can refuse or reject the application if:

- The PVO is “vexatious, frivolous, lacking substance or has no reasonable prospects of success; or

- The PVO could be more appropriately dealt with via mediation

An avo application can be refused by a Registrar or Magistrate

When is an AVO Application Accepted?

A Local Court Registrar or Magistrate will accept or approve an AVO application form, turning it into a provisional AVO, if the allegations made relate to a personal violence offence, or related to conduct amounting to intimidation or stalking with the intention to cause fear or harassment concerning race, religion, homosexuality, HIV, disability etc (only in ‘compelling reasons’ will an application for an PVO be refused in those circumstances).

In deciding whether or not to accept the application for a provisional violence order, the Registrar or Magistrate of the local court will consider the following matters:

- Nature of the allegations

- Whether it can be resolved through mediation

- Whether both parties have tried to resolve it through mediation on a pervious time

- Whether there is availabilities of mediation or ADR options

- Whether each party are willing to try to resolve it through mediation

- Bargaining powers of the parties

- Whether the APVO is a cross application against each other party

- Other ‘relevant’ matters can also be considered

Grounds for a Final AVO

A court will grant the making of a final AVO if the following two requirements are satisfied on the balance of probabilities:

- The protected person has reasonable grounds to fear, and actually does fear that the defendant will engage in domestic violence or will intimidate or stalk the protected person(s); and

- In light of the safety and protection of the protected person (and any child of that person), the AVO orders/conditions are necessary for the safety and protection of the protected person(s).

If the ‘protected person’ in the AVO is a child, for the court to grant a final AVO protecting the child, it only needs to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that the child has reasonable grounds to fear a personal violence offence, intimidation or stalking behaviour by the defendant in the avo. Here the court isn’t required to consider whether the child actually holds fears, see section 16(2) & 19(2) Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW).

Before applying for an AVO, it’s a good idea to contact the Court on 1300 679 272 to find out what your local court’s preference is in making an AVO application.

Some may prefer that you come in and speak to a Registrar, others will be happy for you to complete and file an application form.

Click here for a sample personal violence order nsw application form.

Click here for a sample domestic violence order application form.

For application forms and more details on how to get an AVO, call and speak to one of our specialist AVO lawyers in Sydney & across NSW, or visit more information on how to get an AVO.

Book a free consultation with an experienced lawyer

Who Can Apply for an AVO?

According to section 48, an AVO application can be made by any of the following people:

- The person needing protection referred to as the ‘protected person’

- A guardian of the person needing protection

- Police officer

If the protected person is a child, only a police officer can make an application for an AVO.

If a police officer makes an AVO application on your behalf, the AVO application can also protect more than one person as the ‘protected person’.

If the ‘protected person’ made or makes the AVO application, then the protected person named in the AVO can also ask for the AVO to cover anyone else whom he/she has a domestic relationship with, including children, partner, or other family members.

A person who is between 16-18 years of age can make an AVO application on their own.

Applications for AVO’s can now be made by either attending a local court registry, or your local police station.

A senior police officer can make a provisional AVO on-the-spot, which lasts for 28 days. The AVO will then normally be listed in court within that 28 day period when the court can either dismiss, extend or finalise the AVO.

False or Misleading AVOs

It is a crime to knowingly make a misleading or false statement (in a material particular), orally or in writing if that statement is made to a registrar or Magistrate in making an avo application.

Section 49A Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW) imposes a maximum fine of $1,100 or 12-months jail, or both in addition to a criminal conviction.

How to Revoke or Vary AVOs

Revoking an AVO means to remove it. Whereas to vary an avo means to change the conditions (or orders) of it.

You can apply to revoke or vary an AVO simply by applying to the local court under Division 5 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW).

Any of the relevant parties can revoke or vary an avo, including the defendant, the protected person or the police.

The grounds of the application to revoke or vary must also be outlined in the application before lodging it with the court.

A court can revoke or vary an AVO if:

- Circumstances on which the AVO was initially based on has since changed; and

- The application to vary or revoke it is NOT in the nature of an appeal; and

- It is proper in all the circumstances to revoke or vary the AVO (only applies to private AVOs); and

- A notice of the application has been served to the protected person named in the avo (if the protected person is making the application then the protected person must also serve a copy of the application to the defendant; for police AVOs, a copy of the application must also be served to the commissioner of police); and

- The application must be served personally to the other party or in a manner the court directs.

For private AVOs, if a child is named as a ‘protected person’ in the AVO, the court may notify the Commissioner of Police if the court believes it would be in the best interest of the child- in order to give police an opportunity to appear in the application.

If a Child is Named as a ‘Protected Person’ in the AVO

If a child is named as a protected person in the AVO, the court can revoke or vary the AVO if the following steps are met:

- The Court grants leave (permission), which will occur if:

- There is a significant change in circumstances since the AVO was first made or varied; OR

- It’s in the interest of justice to grant leave; OR

- The application to revoke is made by Department of Family and Community Services (DOCS) on the basis that a care plan for the child is inconsistent with the police AVO; AND

- Notice of the application is served to the Commissioner of Police; and

- There will be no significant increase in the risk of harm to the child; and

- Circumstances on which the AVO was originally based on has since changed; and

- The application is NOT in the nature of an appeal; and

- It’s proper to revoke or vary it in all the circumstances (this only applies to private AVOs); and

- A copy of the application is served to the other part either personally or in the way ordered by the court.

If the application is only to vary the avo (not revoke it), then the safety and protection of the protected person and child will also be considered by the court.

Who Can Revoke or Vary an AVO?

An ‘interested party’ can apply to either revoke or vary an AVO.

An ‘interested party’ includes, the people named in the avo i.e. defendant, protected person, police officer.

How to Remove a Child’s Name From an AVO

A child being named in an AVO as a “protected person” has significant consequences on a defendant named in an AVO for the following three main reasons:

- Restricting access to your child: If you‘re the defendant and the AVO includes your childs’ name as a protected person, the AVO orders can restrict or prohibit you from contacting or seeing your child, or it may allow you to see your child only with supervision- restricting your access significantly for the duration of the AVO.

- Effect on child custody dispute in family court proceedings: An AVO with your child’s named on it can be used against you in any child custody or parenting disputes in Family Court proceedings. This can influence a more unfavourable outcome to you, further restricting access to your child by the Family Court. An AVO is commonly used by the other side against you with this motivation.

- More difficult to revoke or vary the AVO: In the same scenario, the AVO with your childs’ named on it, makes it more difficult for you to later revoke or vary the AVO orders. For AVO’s where the police act on behalf of the “protected person”, you cannot revoke or change the AVO orders/conditions unless the Court grants you leave to even make the application. This imposes an extra hurdle to pass which you would otherwise not need to as a defendant in an AVO.

AVOs involving domestic relationships referred commonly as DVOs automatically extend to protect any child of the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO. This extends to partners and family members.

This means that if you’re a defendant in an AVO with conditions restricting you access or communication to your partner (or ex-partner), the AVO conditions will automatically extend to include the same conditions to protect any child of your partner (or ex-partner). Even if that child is also your child.

You can ask the court NOT to include the child in the AVO if the court can be convinced there are good reasons to NOT include the child as a “protected person” in the AVO.

‘Good reasons’ can include the following circumstances:

- There’s no direct physical violence or threats of violence towards the child.

- There’s no physical violence in the presence of the child.

- The basis of the other side trying to get an AVO against you only involves the use of words, not conduct.

- There’s no allegation of the child ever being present when the conduct complained of occurred.

Breach of AVO

It is a criminal offence to breach any conditions of an DVO or PVO, warranting serious criminal penalties of up to two years imprisonment and/or $5,500 fine prescribed by section 14 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW). section 14(4) of that law requires the court to consider imposing an imprisonment sentence for an AVO breach offence involving violence towards to the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO.

There are two main types of imprisonment sentencing options available, namely:

- Full Time Imprisonment; and

- Intensive Correction Order (ICO), where you don’t go to gaol, but are placed on strict conditions within the community.

What the Police Must Prove

In order to be guilty of AVO breach, the police must prove the following 2 requirements:

- You have breached one or more conditions listed in the AVO; and

- At the time of the breach, you knew that you were breaching it.

A Failure to prove any one or more of the above two requirements will result in the dismissal of the charge.

Defences for Breach of AVO Charges

Available defences to breach of AVO charges include:

- You didn’t realise that you were breaching an AVO condition at the time. i.e. you weren’t in court when the AVO was made and therefore not aware of the AVO conditions, or you didn’t know a person you are prohibited from being near was standing near you.

- Property recovery order: You were complying with a property recovery order to attend the premises of where the ‘protected person’ lives to retrieve your belongings.

- Mediation: You attended a court referred mediation to resolve the AVO dispute, despite the AVO conditions prohibiting you from approaching or contacting the ‘protected person’.

- AVO was not served: You weren’t served with a copy of the AVO conditions, or you weren’t in court when the AVO was made.

- Self defence: Where the breach of avo was incidental to you protecting yourself or someone else or your property.

Consequences of an AVO: What Happens After an AVO?

Here is a list of the potential consequences of having an AVO against your name in Australia:

- Parent child custody disputes in family court proceedings:

- If the allegations in the avo are proven or if you admit to it in court, the Family Court may impose greater child-access restrictions, especially if the evidence shows that the child was either present during the allegations or the child was a victim.

- If the allegations in the avo are not proven in court, yet the avo is finalised against you, the Family Court may impose less child access restrictions on you i.e. if you finalise the avo by consent but without admissions to the allegations.

- The Family Law Act 1975 (Clth) requires a party to a parenting or child custody dispute in court to advise the court of any AVO involving a child or family member of the child. The court is then allowed to take this into account.

- Employment and working with children clearances:

- An avo can prevent you from getting a job involving working with children because it can prevent you from getting a working with children clearance (WWCC).

- An employer may also be more hesitant to give you a job due to the longer process a person with an avo will have to go through for a WWCC.

- The Children’s Guardian will cancel your WWCC if it considers you to be a risk to children safety after it conducts a risk assessment on you. Otherwise it may impose an interim-bar.

- Firearms Licence and Permits:

- As a defendant to an avo, your firearms licence or permit will be suspended automatically upon an interim-avo being made.

- The firearms licence/permit gets automatically revoked if a final avo is made.

- If either of these two things occur, you must surrender your firearm or weapon to the police.

- See section 23 & 24 of the Firearms Act 1996 (NSW), and section 17 and 19 of the Weapons Prohibition Act 1998 (NSW).

- Termination of tenancy agreement: A residential tenancy agreement will be terminated if a final avo is made in court against you if the avo condition stops you as a tenant from accessing or attending the premises (section 79 of the Residential Tenancies Act 2010 (NSW)).

It is common for the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO to use the existence of an AVO against the defendant named in the AVO, to later suggest to the Family Court that the defendant is an unsuitable parent in child custody and parenting disputes.

Family Courts are experienced enough to recognise that some AVO’s are used tactfully in attempts to influence the Family Court to impose more favourable parenting order for one parent over the other.

As a result, in such circumstances, Family Court Judges may give little to no weight to certain AVO’s in child custody disputes, especially if the AVO is consented to by the defendant where the facts are not admitted nor proven.

How to Appeal the Children’s Guardian Decision to Cancel a Working With Children Clearance?

You can appeal the cancellation or refusal of your working with children’s check clearance.

You can appeal directly to the NSW Civil and Administrative Tribunal (NCAT) for an administrative review under the Administrative Decisions Review Act 1997.

You can make this appeal within 28 days after receiving the cancellation or refusal notice.

Where you receive an interim-bar stopping you from working with children temporarily, you can also appeal this decision only after the interim-bar has been in place for at least 6 months.

What is an Interim AVO?

An “interim AVO” is a temporary AVO order imposing conditions in the form of restrictions and prohibitions on a defendant named in the AVO.

Interim avo conditions are legally enforceable. There will be criminal charges if they are breached during the existence of this type of avo.

An interim AVO isn’t a criminal charge, and is not considered a criminal proceeding in court. This means, an interim AVO doesn’t give you a criminal record or conviction.

An interim AVO remains in force until the AVO proceedings are concluded.

An interim avo will conclude or cease to exist if the avo is either dropped, the defendant consents to the avo becoming final, the court dismisses it or turns it into a final ago.

How Long Does an AVO Last For in NSW?

An AVO can last for a period of days to years, depending on the type and conditions of the AVO, explained here:

- Final AVOs: Section 79 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW) says that a final AVO lasts for as long as it says in the AVO. The period imposed by the court can be for “as long as is necessary in the opinion of the Court to ensure the safety & protection of the ‘protected person’.” If the Court doesn’t specify how long it will last for, then the final AVO will remain in force for 1 year from the day it was made in court. A court will normally impose a final avo for a period of 6 months to 2-years.

- Provisional AVOs: Once an application for an AVO is made, it isn’t enforceable until it becomes a ‘provisional AVO’ first. This is what an AVO starts off as on the first court date in an AVO case. The court can then extend this avo past the first court date by turning it into an ‘interim AVO’ or ‘final AVO’. A provisional AVO can only last for the first 28 days from when it gets made. A provisional AVO can be made before the first court date or on the first court date.

- Interim AVOs: An ‘interim AVO’ is often made on the first court date by a Court to extend the period of the AVO, until at least the matter is finalised in court. An interim AVO can last for the entire AVO court case until it gets either dropped, dismissed, or becomes a ‘final AVO’ in court.

Property Recovery Orders in AVO’s

Some AVO’s may have conditions that prevent you from contacting the ‘protected person’, or attending or entering the house where the ‘protected person’ lives in (even though you also live in that house).

This will prohibit you from attending that home despite you needing to go back there to retrieve some of your property i.e. clothes, car, jewellery etc.

Alternatively, the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO may want to retrieve belongings still located in your home.

To be able to safely go to that house to retrieve your belongings, without breaching the avo conditions, you must apply to the court for a ‘property recovery order’.

How to Get a Property Recovery Order in an AVO Case

Section 37 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW) allows you to request the court to can make a ‘property recovery order’, to allow you to attend and retrieve your belongings left at the other person’s home if:

Your personal belongings are left at the other person’s home (named in the avo); and

After disclosing any family law property orders (or pending orders) from the Family Court.

What Does a ‘Property Recovery Order’ Allow You to Do?

A ‘property recovery order’ has the following effect in avo cases:

- It can allow for a nominated person to accompany you to retrieve the items from the house;

- It can require you to be accompanied by a police officer when attending to retrieve your belongings from the house;

- It can specify that the time to attend and retrieve your belonging be pre-arranged by agreement between the person who occupies the house and police officer beforehand;

- The person who resides in the home that your belongings are left in can be directed to allow you access to the house to retrieve those belongings. This includes access to a police officer that accompanies you.

- It can specify the actual items you seek to retrieve back;

A ‘property recovery order’ doesn’t allow anyone to use force to gain entry to the house.

For example, if the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO is granted a ‘property recovery order’ to retrieve some belongings from the defendant’s homes – ‘the protected person’ is not allowed to use force to gain entry even if the defendant refuses entry.

Only the items listed in the ‘property recovery order’ are allowed to be retrieved, nothing else.

What Happens If the Other Person Doesn’t Comply With the ‘Property Recovery Order’?

Non-compliance with a ‘property recovery order’ occurs, for example where the other party to the AVO refuses or obstructs your access to the premises, or prevents you from retrieving your belongings.

Contravening or obstructing a person from trying to comply with a ‘property recovery order’ will result in a fine of up to $5,500.

As a defence to this, you can only breach a ‘property recovery order’ if there’s a reasonable excuse’.

What Happens if the ‘Protected Person’ Named in an AVO Doesn’t Attend Court?

The court has the power to dismiss an AVO in certain circumstances where the ‘person in need of protection’ (PINOP) fails to attend court, as follows:

- Fails to attend the hearing date: If the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO fails to attend court on the AVO hearing date, the Magistrate may dismiss the AVO after proceeding to hearing on the day if:

- The ‘protected person’ named in the AVO had reasonable notice of the hearing date, time and place; and

- It would be in the interest of justice to continue the hearing in the absence of the ‘protected person’; and

- After considering the grounds set in the AVO application and any statements provided to the Magistrate by a police officer (if there is any).

- Fails to attend a mention date: The Magistrate can ‘strike out’ the AVO on a second or subsequent ‘mention’ court date if the ‘applicant’/’protected person’ named in the AVO has failed to serve his/her statement to the defendant on time, and if that person has also failed to attend court. This means, that the AVO can be dismissed by the court- if the other side have failed to appear and have failed to comply with the court orders.

- Fails to attend on first date: If the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO fails to attend the first court date, the Court cannot make an ‘interim AVO’ unless:

- The ‘protected person’ was unable to attend for a ‘good reason’; and

- The interim AVO requires the Court’s urgent attention to consider.

In those circumstances, the Magistrate will be allowed to look at any affidavit or statement given by a police officer on behalf of a ‘protected person’.

What Happens if the Defendant Named in an AVO Doesn’t Attend Court?

The court has the power to make a decision adverse to the defendant named in the AVO if the defendant fails to attend court in certain circumstances outlined below:

- Fails to attend the hearing date: Where the defendant fails to attend, but the ‘applicant’ or ‘protected person’ named in the AVO attends court for the AVO hearing, the court can make a final AVO against the defendant. The Court can do this after it proceeds to hear the AVO on the day, if each of the following are satisfied:

- The defendant had reasonable notice of the hearing date, place and time; and

- It’s in the interest of justice to proceed with the AVO hearing in the absence of the defendant; and

- After the court has considered the grounds set in the AVO application, and any statements provided from a police officer.

- Fails to attend court on a mention date: The Magistrate may make a final AVO against the defendant on a second or subsequent ‘mention’ court date if:

- The defendant has failed to comply with the orders made by the court from the first court date; and

- The defendant has failed to attend court on the subsequent ‘mention’ court date (to determine compliance with court orders).

What Happens if You Fail to Comply with Court Orders in an AVO Case?

If you’ve failed to comply with court orders to serve your statement(s) or other evidence to the other side on time, you will generally NOT be allowed to rely on evidence you then wish to put forward on your hearing date in court, unless the court grants you leave (permission) to use this evidence in court.

The Court will only allow you to put forward your evidence if it considers it to be in the interest of justice.

If the court refuses to allow you to give your evidence i.e. oral evidence in the absence of having served a written statement, the court can decide the AVO in favour of the other side.

Is an AVO a Criminal Conviction?

An AVO is a civil proceedings by nature, and is therefore not a criminal proceedings. Therefore, an AVO is not a criminal conviction. A breach of an AVO condition will result in a breach of AVO criminal charge, which can result in a criminal conviction unless it gets dismissed in court.

Does an AVO Go on Your Record?

Does an AVO Show up on a Police Check, and is AVO civil or criminal?

An AVO is a civil proceeding in court. It’s NOT a criminal charge, therefore it’s NOT a criminal proceeding.

AVO’s can have many other unforeseen consequences, it WON’T show up on a police background check, such as a national police check.

Will an AVO affect my job? An AVO will show up if you’re trying to get or maintain a working with children clearance check.

An AVO is considered in a working with children clearance check by the Childrens’ Guardian.

If you were to breach an AVO by failing to comply with its conditions, then the AVO will become a criminal offence, resulting in a criminal charge against you. If you’re found guilty for the charge of breaching an AVO, then it becomes a criminal proceeding, which will show up on a police check.

How Long Does AVO Stay on Record?

A final AVO can be imposed by a court for as long as the court deems necessary to secure the safety and protection of a protected person. If the court fails to specify the length of the AVO, then it will remain in force for 12 months. Court’s routinely impose AVOs for between 6 months to 24 months. Breaching an AVO during the term of the AVO results in a breach of AVO offence which becomes a criminal proceeding. Urgent legal advice from an experienced lawyer is highly recommended before talking to police.

It is important to know the comparison between a final AVO, a provisional AVO, and an interim AVO.

Can you Travel Overseas with an AVO?

Having an AVO against you will normally NOT prevent you from traveling overseas or interstate.

AVO’s, whether interim or final, are not criminal in nature. AVO’s are civil cases usually dealt with by a Magistrate in the Local Court.

Breaching an AVO, on the other hand, is a criminal charge, and can affect travel.

Example of the Court Making a ‘Timetable Order’ in AVO Cases

Where the defendant opposes an AVO in court, it means he/she is contesting it from becoming ‘final’. In that case, the Court will make the following type of order, called a ‘timetable’:

- The “applicant” or “protected person” named in the AVO paper is to serve written statement(s) intended to be used as evidence in 2 weeks, usually from the first court date.

- The defendant named in the AVO is to serve written statement(s) in reply (intended to be used as evidence) in 4 weeks from that court date.

- The case will then be adjourned for 5 weeks to a second or subsequent court date for ‘mention’ or ‘compliance date’ in order for the court to be updated on whether parties have complied with these orders.

Where the defendant and “protected person” named in the AVO are not legally represented, each party are to serve their written statements (or other evidence) to the court registry, where it can be collected by the other party.

The defendant in the AVO won’t be able to serve their statement/evidence in reply, UNLESS the other side serve their statement and evidence first.

How to Get the Other Side to Pay Your Legal Costs in AVO Cases

How to Win Costs in AVO Cases?

It isn’t easy to convince the court to order the other side to pay your legal costs or fees, but it’s definitely achievable and has been achieved in court many times.

To successfully achieve this, it’s important to understand and be familiar with the AVO laws.

Below is a guide on how to get the police (or ‘protected person’) to pay your legal costs in an AVO case.

Getting costs in AVO cases require experienced AVO lawyers to carefully prepare and persuasively present your case for costs in court.

Types of Cost Orders in AVO Cases

The law on costs in AVO cases is section 99 of the Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW) which give the court the power to order costs against the police in any of the following circumstances:

- Cost on the adjournment: The court can order that the alleged victim/protected person or the police officer in the AVO pay your legal costs for arranging a lawyer to appear in court for you, if that court date ends up being adjourned to another date due to the other sides ‘unreasonable conduct or delay’. An example of this is where your case ends up getting adjourned to another court date due to the other sides fault(s)- the other side’s continued failure to comply with court orders (Section 99 Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW)).

- Cost against the ‘protected person’: The court can order that the alleged victim (who made the AVO complaint) pay your legal costs in the AVO proceedings where:

- The alleged victim who made the AVO application didn’t have sufficient grounds to make the AVO; or

- Where the AVO served only to cause annoyance; or

- Where the AVO application lacked seriousness.

- Costs against police: The court can order that the police (who made the AVO application on behalf of the alleged victim (protected person)) pay your legal cost in the AVO proceedings if the court is satisfied that either one or more of the following occurred:

- The police officer made the AVO application knowing it contained false or misleading information; or

- The police officer has ‘deviated from the reasonable case management of the proceedings so significantly as to be inexcusable’. i.e. Where the police continuously fail to serve important parts of the brief of evidence in breach of court orders.

Where the AVO is related to a criminal charge, section 214 Criminal Procedure Act 1986 (NSW) allows the court to order the police prosecutor to pay your legal fees if:

- The investigation of the allegations was unreasonable and improper in the manner conducted by police; or

- The AVO proceedings started without reasonable cause, or in bad faith, or it was conducted by the prosecutor in an improper manner; or

- The police prosecutor unreasonably failed to investigate a relevant matter which if aware, or aught reasonable to have been aware, which suggested you might be ‘not guilty’; or

- Due to other exceptional circumstances relating to the conduct of the proceedings by police, it’s just and reasonable to award costs.

These types of charges with avo’s are referred to as domestic violence charges. If you’re facing this, get in touch with our domestic violence & AVO lawyers in Sydney today.

Example of Getting Legal Costs Awarded in An AVO Case

AVO costs can be claimed upon making a cost application in court. The case of Rodman v Willcocks [2010] is a commonly cited case in cost applications. This case was a Supreme Court decision considering the issue of legal costs in an AVO case. The court said that because the person who made the complaint told the police officer that she no longer feared the defendant, the police then confirmed with the defendant that this was true, but advised the defendant that appropriate paperwork had to be done to confirm whether the AVO was to be dropped or not.

The police did not end up confirming the withdrawal of the AVO, which caused the defendant to pay a lawyer to attend court for the hearing day on the basis that it was highly probable that the matter would still proceed. The police had failed to undertake the necessary paperwork which was sufficient grounds for the court to order costs against police.

In this case, the costs order was made due to the procedural failures by the police, which caused the defendant to incur legal costs of having his lawyer appear on the AVO hearing day in court.

Can the Defendant Get Costs Awarded if the ‘Protected Person’ Named in the AVO Fails to Attend Court or Doesn’t Want the AVO?

Generally, a police officer (who made the AVO application on behalf of the ‘protected person’) CANNOT be ordered to pay defendant’s legal costs in DVO proceedings if the police officer made the AVO application in good faith, even if the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO does any one or more of the following:

- Indicates to police that he/she will be giving unfavourable evidence in the police case.

- Indicates to police that he/she doesn’t want the AVO.

- Indicates to police that he/she holds no fears from the defendant in the AVO.

- Attends court and gives unfavourable evidence in court.

- Doesn’t end up attending court to give evidence for police.

Generally, the ‘protected person’ named in the AVO cannot be ordered to pay the defendant’s legal costs in the apprehended domestic violence order or apprehended personal violence order proceedings if the ‘protected person’ simply fails to appear in court.

What Happens at an AVO Hearing?

A contested AVO hearing is called a ‘show cause hearing’ in the Local Court.

Written Statements as Evidence in Court

All evidence is given by written statement(s) by each party in court, namely the ‘protected person’ and the defendant give their evidence through written statements.

The written statements are required to be served to each party before the hearing day.

This means, the ‘protected person’ (or police, or lawyer acting on behalf of the ‘protected person’) is required to serve their written statements to the defendant in the AVO. The written statement is meant to form the basis of convincing the court to make a final AVO against the defendant.

After the defendant receives a copy of that written statement, the defendant will then be required to draft and serve a copy of his/her own written statement in reply to the other side.

Opening of the Applicant’s Case

On the avo court hearing, the ‘protected person’ will rely on his/her written statement to the court as ‘evidence in chief’.

The Presiding Magistrate will read that statement. After this occurs, the ‘protected person’ while in the witness box of the court room will then be subjected to questioning by the defendant (or defendant’s AVO lawyer). This questioning is called ‘cross-examination’.

During cross-examination, the defence will test the ‘protected person’s’ evidence so far and outline inconsistencies. If this is done well by an experienced AVO lawyer, it can create significant doubts in the other side’s case, leading the court to disbelief the ‘protected person’s’ version.

After the ‘protected person’s’ cross-examination is complete, the same process will occur for any other witnesses for the ‘protected person’s’ side.

After all this evidence is concluded, the Defendant will be asked to open its case. The defendant is not necessarily required to give evidence, but can choose to do so.

Whether or not the defendant chooses to give evidence in reply really depends on the ‘protected person’s’ evidence. Generally, the defendant ends up choosing to give evidence.

Opening of the Defendant’s Case

Once the all evidence has been given and subjected to cross-examination, the defendant will get into the witness box of the court and rely on his/her written statement during the hearing. This will be considered the defendant’s evidence in chief.

The Magistrate will read the defendants’ written statement.

After this, the defendant will then be subjected to cross-examination by the ‘protected person’ (or either the police prosecutor, or lawyer acting for the ‘protected person’).

During cross-examination of the defendant, the other side will try to test the defendant’s version, while attempting to raise inconsistencies in order to try to convince the court to not accept the defendant’s version.

At the conclusion of the defendant’s evidence, the same process will occur for any of the defence witnesses.

Where a child is a witness in an AVO hearing in court, the defendant is not allowed to cross-examine the child. The cross examination can only be done by the defendant’s legal representative or a suitable person appointed by the court (s41A). This is important to remember if your case involves a child witness.

After the defence evidence has all been given in court, the defence will close its case.

Submissions in Court at the Conclusion of All the Evidence

Once both sides have closed their cases, the Magistrate who has heard both sides of the evidence will decide whether or not to make a final avo order.

The Magistrate will then either dismiss the AVO, or order an final AVO against the defendant with conditions. Either way, the AVO case will then come to an end.

Can I Appeal an AVO?

There are two main types of AVO appeals in NSW, namely, an appeal to the District Court, and a review by way of an annulment of the local court decision to make or dismiss the avo application:

- AVO appeal to District Court: A defendant or applicant (‘or protected person’) has a right to appeal a local court’s AVO decision if the Local Court has done any of the following:

- Made an avo; or

- Dismissed an avo; or

- Varied or revoked an avo; or

- Refused to vary or make an avo; or

- Costs order

If a defendant has consented to an avo in court, yet later wishes to appeal that avo, then the District Court’s permission will first be required in order to be allowed to appeal (section 84(2) Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW)).

- Annulment Application in Local Court: A defendant can apply to the local court to annul an avo order that was made in the absence of the defendant in court, if:

- The defendant wasn’t aware of the original court date at the time the avo order was made; or

- The defendant was hindered by illness, accident or misadventure or other reason from taking action when the original court made the avo decision; or

- It is in the interest of justice given the circumstances.

An applicant, such as the ‘protected person’, or police or lawyer acting for this person can ask the court to annul the original order by the local court to dismiss the avo, if the avo was dismissed in that person’s absence in court, and if there is just cause for doing so given the circumstances (Section 84(1) & 84(1A) & 84(1B) Crimes (Domestic and Personal Violence) Act 2007 (NSW)).

Book a free consultation with an experienced lawyer

Book a Lawyer Online

Make a booking to arrange a free consult today.

Call For Free Consultation

Call Now to Speak To a Criminal Defence Lawyer

Over 40 Years Combined Experience

Proven SuccessAustralia-Wide

Experienced LawyerGuarantee

(02) 8606 2218

(02) 8606 2218

(02) 8606 2218

(02) 8606 2218