Share This Article

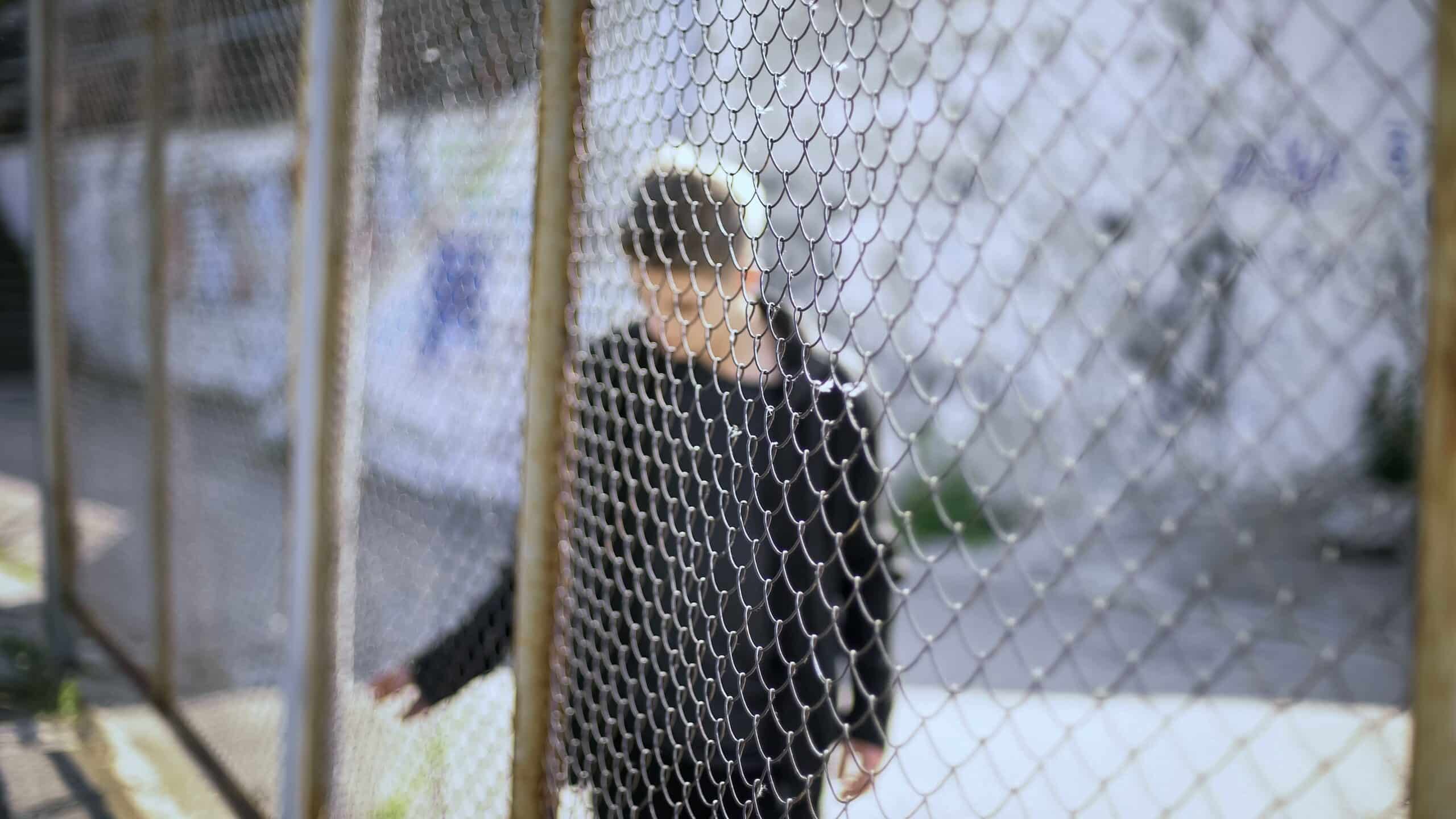

The New South Wales Government has announced new bail laws which will lead to more young people being held in custody, by making it harder for teenagers to be released on bail.

The proposed change has been labelled as a ‘knee-jerk law and order’ response by advocates amid concerns of raising youth crime rates in regional areas, specifically Moree in northern NSW.

The bill is the ‘Bail and Crimes Amendment Bill 2024’ which seeks to insert section 22C into the Bail Act 2013 (NSW).

This section provides for an extra test relevant to granting bail for 14- to 18-year-olds who have been charged with a serious breaking and entering offence (those which are punishable by a maximum penalty of 14 years imprisonment or more) or a motor vehicle theft offence, whilst on bail for the same offences and seeking further bail.

It specifies that the bail authority (i.e., police, Magistrate or Judge) “must have a high degree of confidence” that the young person will not commit a serious indictable offence if bail is granted.

A ‘serious indictable offence’ refers to an offence carrying a maximum term of imprisonment of five years or more.

The limitation is proposed to operate temporarily and expire 12 months after the proposed section commences (referred to as a ’12-month sunset clause’) so that any further action can be made with evidence to assess the efficacy of the new laws.

Attorney General, Michael Daley noted: “we are introducing some important legislative measures that respond to the immediate concerns expressed by our regional communities about repeat offending on bail and dangerous crimes being committed, and then filmed and disseminated.

“What we really hope to see from this package of reforms is the positive impact of the prevention and intervention measures, so that we see fewer young people entering the criminal justice system.”

Whilst Daley conceded that he was concerned that the laws would result in more young people being held behind bars, he remarked how: “if there was another option available to us today, to keep these children safe, we’d take it. But there isn’t.”

The move has been heavily criticised by organisations including the Greens, the Law Society of NSW, and the Aboriginal Legal Service.

“Despite claiming the bail amendment is ‘cautious’ and ‘careful,’ the government’s response appears to be the opposite. The government has chosen to ignore years of work by communities with on-the-ground experience in favour of a clumsy and misguided appeal to the headlines.” noted criminal defence barrister, Caitlin Akthar.

“The proposed changes make our communities less safe. Remanding youth has been proven time and time again to increase re-offending – essentially, the effect is to encourage crime. It would be hard for the NSW government to pick a more effective way to increase youth crime than by this amendment.” she continued.

Karly Warner, CEO of the Aboriginal Legal Service, remarked how the organisation was “devastated the NSW Government will move ahead with dangerous changes to bail laws for children.”

She explained how: “these knee-jerk actions will only make communities more dangerous. You only need to look at Queensland to see this will be an unmitigated disaster. It’s also a huge betrayal of Aboriginal communities and goes against everything the Government has promised under Closing the Gap.”

There has been an increasing number of First Nations children in custody in NSW. There are 122 First Nations children in custody, which is an increase of 28.4% in the 12 months to March 2023.

A large majority (75.4%) of those children are on remand (i.e., refused bail).

In New South Wales, the law related to whether bail is granted or refused is set out by the Bail Act 2013 (NSW). If the person applying for bail is under the age of 18, additional considerations under the Children Criminal Proceedings Act 1987 (NSW) are also relevant.

A bail authority (i.e., police, Magistrate or Judge) must refuse bail if it is satisfied that, with reference to specified bail concerns, that the accused poses an unacceptable risk.

Unacceptable risks include that the accused, if released from custody, will:

- fail to appear at any proceedings for the offence,

- commit a serious offence,

- endanger the safety of victims, individuals, or the community, or

- interfere with witnesses or evidence.

These risks are also referred to as bail concerns. If the court has concerns that an accused person’s release from custody may enliven any such risks, it must then consider whether any conditions could be imposed to mitigate this. If there are no conditions possible of doing so, bail must be refused.

This test (referred to as the ‘unacceptable risk test’) is applicable for both adults and young persons.

However, where an adult has been charged with certain serious offences (as listed under section 16B of the Bail Act and referred to as ‘show cause offences’) they are required to ‘show cause’ as to why their detention is not justified, before the application can proceed to the ‘unacceptable risk test’.

A child who applies for bail for an offence that would otherwise be considered a ‘show cause offence’ is not required to ‘show cause’.

Bail conditions can only be imposed where there are identified bail concerns, and the proposed bail conditions are:

- reasonably necessary and appropriate to address a bail concern,

- no more onerous than necessary to address the bail concern in relation to which it is imposed, and

- reasonable and proportionate to the offence for which bail is granted.

It must also be satisfied that the conditions are reasonably practicable for the accused person to comply with, and there are reasonable grounds to believe that the condition is likely to be complied with by the accused person.

This is important to consider when bail conditions are imposed on children.

For example, a young person may face issues in reporting at a police station or attending court in circumstances where they don’t have a driver’s licence, there is a lack of public transport, and they are faced with parental dysfunction or homelessness.

If a court seeks to grant a young person bail, however, the child has no accommodation, it can grant bail with an ‘accommodation requirement’ under section 28 of the Bail Act.

In accordance with this requirement, the court may direct any officer of a Division of the Government Service to provide information about the action being taken to secure suitable arrangements for accommodation of an accused person.

This usually involves Youth Justice or the Department of Communities and Justice (previously known as DoCS or FaCS).

If this is imposed, the court is required to re-list the matter for further hearing at least every 2 days until the accommodation requirement is complied with.

Bail applications for young persons will generally be heard before the Children’s Court. The Court has specific bail guidelines.

These guidelines refer to how contact with the criminal justice system is harmful for young people, and even short periods in custody can significantly increase the likelihood that a young person will reoffend.

It also confirms how the central task in the bail determination is to assess risk, however, this is limited to the bail concerns, outlined above.

Bail cannot be refused merely due to the child having a drug problem, unaddressed welfare issues, being at risk of self-harm, or due to the child not complying with their parents or carers.

Whilst the Court recognises that such matters evidently must be addressed, this must come from an appropriate agency and not through remand. This highlights how the Court seeks to avoid a custodial setting being utilised to cover a gap in the provision of welfare services.

Therefore, the decision to refuse bail to a young person, or to impose bail conditions, should not be made lightly.